Use #SCHMVP to share your good times on Instagram & Facebook for a chance to win!

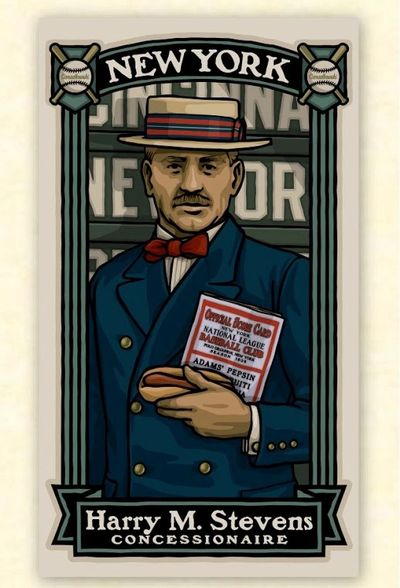

Who is Scorecard Harry?

Harry M. Stevens the Visionary

Had only the late-19th-century citizenry of Ohio been more receptive when Harry Moseley Stevens knocked on their doors selling the complete works of Shakespeare, he might not have been forced to popularize the baseball scorecard. But they weren't, so he had to, and he didn't stop there. By the time he had moved his scorecard empire east to New York, he was well on his way to popularizing the ballpark hot dog as well. Scorecards and dogs. Between them, it is unlikely anyone who has ever attended an American sporting event has been untouched by the legacy of Harry Stevens. WHICH MAKES it mildly ironic that Stevens was born a Brit. He didn't ferry his family across the pond until 1882, when he was 27 years old, with no plan other than to support them, which is what he was attempting to do by carting boxes of Shakespeare door to door. Somewhere along the way he developed a fancy for this new American game of base ball, and one afternoon, needing a break from pitching "Othello," he decided to catch an Ohio State League game featuring the Columbus nine. As he watched, being a man of active mind, he began musing on the scorecards with which fans identified players and kept a running account of the game. The father of this modern scorecard, it is generally writ, was newspaperman Henry Chadwick, who built his card on a scoring system devised by colleague M. J. Kelly. The system assigned each position a number - 1 for pitcher, 2 for catcher and so on - and recorded each at-bat with a shorthand notation in a small box. "HR" meant home run, "BB" meant a base on balls, or walk. A strikeout became "K" because Chadwick had used "S" for a sacrifice hit. Stevens was less interested in the code, however, than in something else. Here, he said to himself, was a fertile and wholly untapped advertising medium. He found the owner of the park and offered $500 for the exclusive rights to produce and sell scorecards. The owner, doubtless viewing this as found money, said sure, Harry. By the time they signed a formal deal, Stevens had lined up $700 worth of advertising, with more where that came from. How much more, even Stevens probably had no idea. Scorecards led him to food, and he moved so quickly and effectively to dominate these areas that 69 years after his last out, the name Harry M. Stevens is virtually synonymous with scorecards, peanuts and workingman's beverages at rich man's prices. IF IT'S any consolation to the captive audience that buys ballpark concessions, Stevens wasn't just some random marketing executive. He was an enthusiastic sports fan, enamored of baseball and especially proud of a picture that showed his good friend Babe Ruth hitting his 60th home run. "To my second Dad, Harry M. Stevens," the picture was inscribed. "From Babe Ruth, Dec. 25, 1927.

" It wasn't an inscription Stevens would have grown up expecting. He was born in London in 1855 and achieved some fame as a child preacher. But in 1882, he bundled his wife and 2-year-old son onto a boat for New York, pausing there only briefly before moving them on to join Ohio relatives. After nine months in a steel mill, the well-educated and well-spoken Stevens began searching for ways to make easier money, and more of it. Shakespeare didn't take care of that. Scorecards did. Some reports say he began selling food at the same time he launched scorecards. Others say he moved into food only after securing the scorecard concession at other parks, including those serving the major league franchises of Toledo and Pittsburgh. Whatever the chronology, in Pittsburgh he teamed with Ed Barrow, who would later become president of the New York Yankees but would always regret leaving the partnership with Stevens. By the early 1890s, Stevens was running scorecard and food concessions from Boston to Milwaukee. Arriving in New York in 1894, he took over the concessions at the Polo Grounds, where at first he sold the standard ballpark foods of the day, lemonade and sandwiches. But those didn't move so well on cool days, and legend has it that Stevens finally sent his vendors out to load up on "hot dachshunds," popular German sausages sold warm. Robust as this story has proven in urban lore, it's likely that the methodical Stevens launched his new product line in a more systematic way. But whatever the idea's genesis, it was a home run, and Stevens added a winning touch of his own. Instead of making the customer figure out how to handle the little critters, he wrapped them in a bun. AS THE 20th century dawned, then, Harry Stevens ruled scorecards and dogs. He landed the concessions at Ebbets Field, Yankee Stadium and race tracks from Belmont to Saratoga. He catered polo matches and six-day bike races, and he said his secret was knowing the customer. "Baseball crowds are great consumers of hot dogs, peanuts and bottled drinks," he said. "Heavier food is popular at race tracks. Prizefight crowds go in for mineral waters, near-beer and hot dogs. A boxing crowd is also a great cigar-consuming crowd. Chocolate goes well in spring and fall, but the hot dog is the all-year-round best seller.

" He set up his offices at Madison Square Garden, Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds, where he used that booming, resonant voice of his preacher youth to direct the troops. Most of his time he spent at his suite in the Waldorf, courting a high-level circle of corporate clients, politicians, business executives and ballplayers. He eventually moved to an apartment at the Murray Hill Hotel, where he died May 3, 1934. So many sports notables attended his funeral, an estimated 500, that someone should have been selling scorecards.

- The New York Daily New

Illustration by: Gary Cieradkowski